Around the world, the system of patents that governs new ideas and technology can seem practically designed to mislead people, making them think that they can see the field clearly when in fact much of what’s visible is an illusion—truly vital information remains hidden. In an environment where incomplete information about tech and IP often causes executives to make costly errors and miss huge opportunities, the problem is a vexing one. And in the course of our work, we see companies struggle with it in a handful of broad areas:

- Finding prior art – evidence that an invention or idea already exists

- Patent analytics – the mapping and analyses of all patents, patent applications, and research publications in a given industry or region

- Patent commercialization – the monetization of IP portfolios

On the bright side, the solutions to each of these challenges share one basic ingredient. No matter the category, every successful IP analysis begins with an exhaustive, fine-grained digital search. It has to be broad enough to ensure it covers the entire scope of relevance—taking in patent databases, academic and corporate archives, repositories of mainstream and industry publications, and more—but discerning enough to screen out the noise and provide a clear picture of what’s happening. To assist us we’ve developed proprietary machine learning software, which we’ll detail below.

Without a broad, powerful search as a first step, the results of an IP research project are sure to be skewed. But even a well-designed search can fall short on the answers a researcher might be looking for.

Through trial and error, we’ve come to believe that in IP research, as in treasure hunting, mere searching isn’t enough. After all, when you’re looking for gold that’s deeply and cleverly buried, you’ll often come up empty-handed, no matter how sophisticated your metal-detecting technology. But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing there.

Over time, we’ve developed an Investigative Approach to IP research, which we’ve honed to address the knottiest IP conundrums—red herrings and optical illusions, hard-to-find evidence, and unlikely connections.

We consider it at least as important as our tech solutions. In fact, we think of it as our guiding philosophy. Although we’re still learning, we’ve found that an investigative approach is the optimal way to solve IP research challenges, whether they pertain to prior art, patent analytics, or patent monetization. In this article, we’ll outline how the approach works. We’ll also demonstrate how to apply it to your IP challenges, giving specific examples of how it has helped us.

What Makes IP Searches So Difficult Anyway?

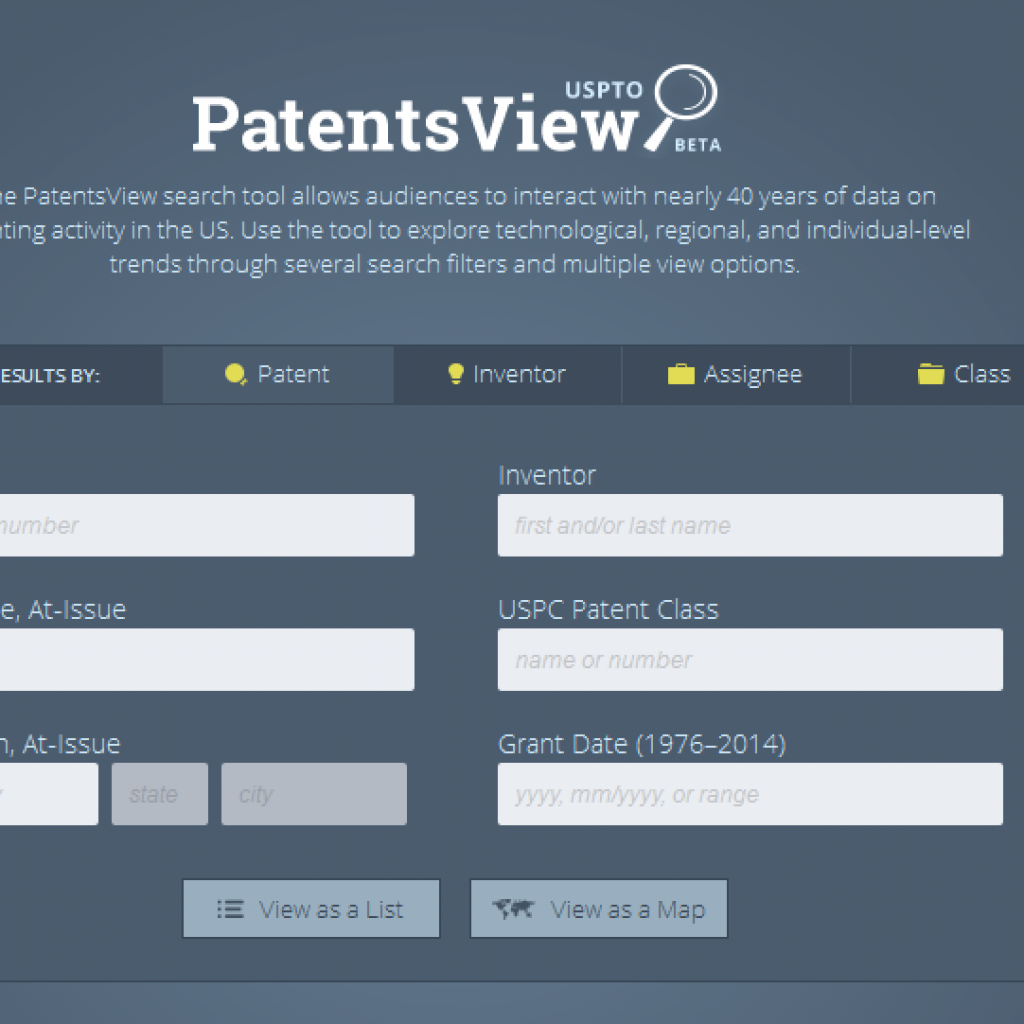

In theory, practically every scrap of global data concerning existing or technology is publicly available. Numerous databases compile up-to-date information from the national patent offices where patents are filed, evaluated, and granted. They make it available either free or by subscription. As we mentioned earlier, strong IP searches don’t stop at patents.

Researchers must also dig deep into academic, mainstream, and industry publications databases, scan government repositories of user manuals and regulatory guidelines, and even consult sources like online message boards and reviews if that’s where the trail leads.

But living in a world in which digital searches often seem to put everything we need at our fingertips can be misleading, especially when it comes to IP research. In reality, complete, accurate IP data is hard to come by. And acquiring it often depends on finding evidence that’s buried far from view. Sometimes it gets that way by accident—other times on purpose.

Reason 1: New Technology Has Ambiguous Terms

When an idea or technology is new, there is often little agreement about how to describe it. Researchers and inventors working on related projects in different parts of the world use radically different terminology: A professor at Harvard might use one set of words, researchers in Tokyo another; a team of inventors in Munich might have a third way of discussing similar ideas. This makes it difficult for their projects to connect via keyword-based searching on which IP research is based.

Reason 2: Companies Deliberately Obscure

Other situations involve deliberate deception. To avoid being identified by competitors, companies file patents using willfully unclear language—describing a particular process vaguely, for example, as an “element” or “agent”—or in terms so deconstructed as to be unrecognizable: a paper clip might be characterized as “a thin, bent rod for holding flat sheets.” To disguise their IP-dependent plans, big companies often file patents in the name of little-known subsidiaries.

In a recent case-in-point, a client asked us to evaluate all of the patents and patent applications in association with Amazon. The client, an Amazon competitor, wanted to know:

- What kind of an IP gap existed between them

- What sectors Amazon appeared to be focused on

- What direction they seemed to be heading in within those sectors

Once we’d gathered that intelligence, we could advise the client on how best to proceed—whether it might make sense to mirror Amazon’s strategy, for example, or if it would be more advantageous to work around them. But in the course of our search, we found what we initially took to be a false positive: a patent belonging to an entity called Modilis Holdings LLC. We had never heard of Modilis Holdings, but with some further research, we found that they were a very small, somewhat mysterious company, composed of just a few researchers.

At first, we saw no reason to believe that they had anything to do with Amazon. We suspected that the Modilis result was simply a database glitch—these things happen—but in keeping with our Investigative Approach, we decided to make sure. Further searches surfaced an article naming Modilis Holdings’ scientists. By using those names as keywords in yet another round of searches, we verified the link: In fact, Amazon had acquired Modilis Holdings around 2009, in an unpublicized deal.

They held some 20 additional patents similar to the one that had popped up in our search, all concerning display-related technology. Finally, we found that the Modilis display technology had been introduced to the public around 2013, via the Amazon Kindle. Needless to say, we informed our client that going forward, they’d be well advised to keep an eye on the activities of Modilis Holdings LLC.

Why Good IP Research Requires Full-Scale Investigations, Not Just Searches

In part, an investigative approach to IP research is a matter of knowing where and how to search—a knack, usually born of experience, for looking in unexpected places. Like Sherlock Holmes, we believe that “from a drop of water a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other”. As in the case of the Chinese cell phone, the Investigative Approach often has us following hard-to-decipher trails of clues—venturing out, away from our screens, to do hands-on research.

In another recent example, a large telecom client asked us to find prior art for a technology patent concerning inter-circuit communication. The owner of the patent hoped to extract fees from our client in exchange for using the patented technology. Our task was to invalidate the claim by proving that the patent’s underlying idea was old—that the technology wasn’t truly novel and that the patent should never have been granted in the first place.

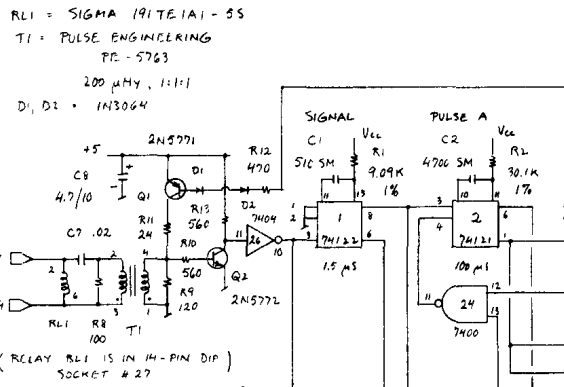

After an exhaustive search surfaced hundreds of thousands of patents that were more noise than signal, we decided to create a mock-up of the circuitry right in our office. By looking at our model, we quickly discovered that by necessity, the technology in question involved a component known in electronic slang as a “one-shot.”

The one-shot, which generates an outgoing pulse, is an incredibly common element. With a little more digging, we concluded that the missing signal wasn’t much turning up in searches because to electronics professionals, its inclusion was so obvious as to make mentioning it redundant.

Still, to invalidate the patent, we had to locate some reference to the one-shot, paired with another component, before 2003, when the patent was granted. And for that we had to go all the way back to 1970, where we found it buried in the appendix of a PhD thesis.

We’ve found that it’s best to begin every assignment with the belief that there’s more to the story than meets the eye. This is a key principle of the Investigative Approach, and almost invariably, applying it turns up data that previous evaluations have missed, whether it’s deployed to find prior art, to perform a patent analytics assignment, or to gauge the monetization potential of a patent portfolio.

To read more about how we’ve applied our Investigative Approach in another context, you can check out a patent landscape analysis we recently conducted of the goldbal smartwatch industry here.

How to Use Machine Learning to Take the Investigative Approach to the Next Level

At some point at GreyB, we realized that we weren’t doing a good job of cataloguing our institutional knowledge, or of making that knowledge readily available to all of the members of our team. The error was significant, preventing us from bringing the hard-won wisdom of our collective experience to bear. No matter how many IP investigations an analyst has conducted, after all, they are inevitably limited by the particulars of their individual resume.

To address this shortcoming, we began developing a set of machine learning tools (described below) that would allow our team members to draw on the full scope of GreyB’s previous work—all of our lessons learned. We designed the tools to incorporate the investigative philosophy outlined above, pointing our analysts toward the unlikely nooks and crannies where IP answers are often found. In an effort to train our technology to think and grow like a member of our team, we emphasized the same aptitudes we look for in new hires: keen observation, rigorous logic, deductive reasoning.

The result is a mutually reinforcing feedback loop, and these are three of the machine learning tools we rely on—and which rely on us—most. Because they depend on our specific experience, they aren’t easy to replicate. But incorporating the thinking that went into them should help other IP researchers sharpen their own searches.

Here are some components and use cases of our machine learning tools and how they assist in our Investigative Approach. (Note: If you’re interested in using these tools yourself, you can contact us here.)

Past Projects: Accessing Detailed Histories of Entire Industries

We think of Past Projects as a kind of massive parallel brain. A searchable database contains not only all of the informational data relevant to all of the assignments we’ve worked on, but the logical analysis that our team members used to bring those assignments from kickoff to conclusion. Put another way, it’s a constantly evolving mind containing everything a GreyB analyst has learned, and how they learned it. It’s an invaluable resource as we tackle new investigations, allowing team members who might lack expertise in a given area to bring themselves quickly up to speed.

Should one of our team members input a query about 5G technology, for example, Past Projects will pull up all of the related work we’ve done in the past, as well as all of the work that the software deems relevant, even if it doesn’t appear connected. A 5G search, for instance, might encourage the analyst to have a look at the GSM standard for early 90s European cellular networks. Past Projects will also suggest investigative strategies, shortcut solutions, and tips about the likely location of strong evidence—in the meeting minutes of a regulatory board, say, rather than academic archives.

Perhaps most valuably, Past Projects includes detailed histories of the technological evolution of whole industries, allowing us to pinpoint how, when, where, and why ideas emerged. Cracking prior art cases often requires delving deeply into the past; the solution to a 5G case may well lie hidden somewhere in those 90s GSM protocols. And Past Projects allows us identify it infinitely faster—a boon to a client with costly litigation and/or licensing fees on the line.

Central Search: Producing Webs of Connections from a Single Keyword

Largely for the reasons we mentioned earlier—the use in patents of deliberately opaque or misleading language, the lack of consensus about terminology for new technology and ideas—simply figuring out effective IP search keywords can be nightmarishly complex. Given that keywords represent the building blocks of any search, regardless of what database you’re using, that presents a problem, which we’ve addressed with something we call Central Search.

Of course, an exhaustive query can be built manually. Scanning patents surfaced by a search for “iPod,” for example, you would develop a list of related terms: MP3 player, portable, personal stereo, etc. Added to the original query, each new term would make the search broader and stronger.

But this process would be incredibly time-consuming and, as in the case of Past Projects, we eventually realized that we had a valuable trove of experience that we weren’t tapping.

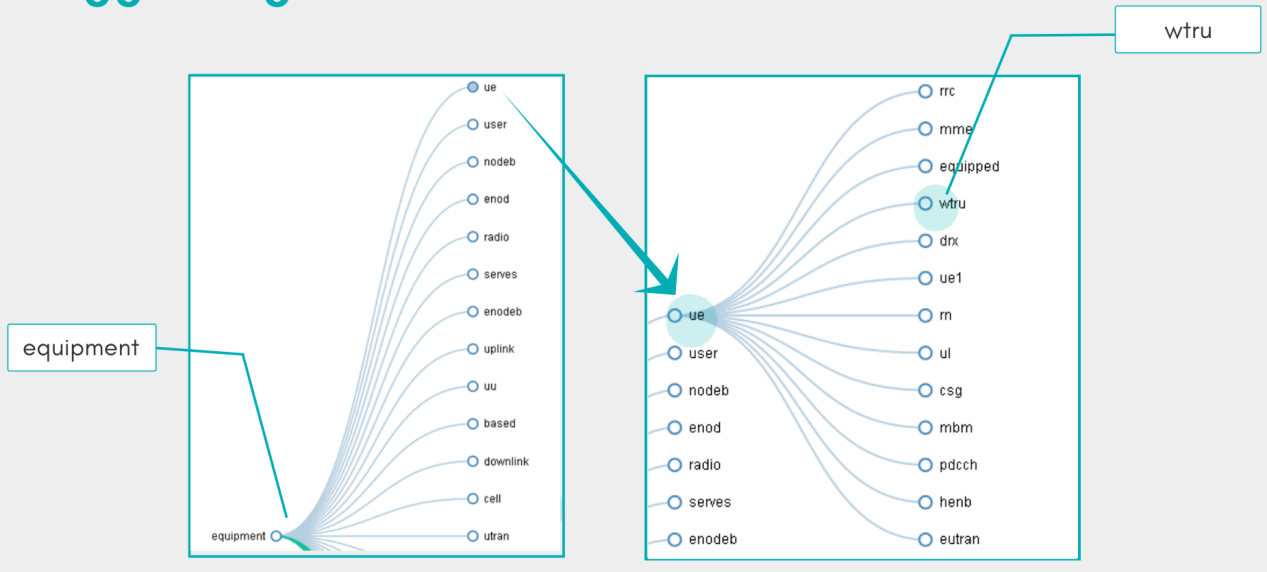

Based in part on the tens of thousands of searches that we’ve run in the past and in part on data available publicly via patent databases, Central Search takes a single keyword and instantly produces blooming webs consisting of many dozens of related terms. For example, a search for “mobile” will surface a host of terms used in patents related to mobile technology and suggest them as potential search-strengtheners. Based on the specifics of a researcher’s task, they will select the most appropriate additions and discard the others.

If “PDA” applies to the IP project, for instance, but “cordless” does not, they’ll use only “PDA” to refine their search. Central Search stores each such decision, subtly adjusting its algorithms. The next time an analyst runs a related search, their results will be influenced—improved upon—by all of Central Search’s previous activity in the subject area. In effect, the tool reflects the collective intelligence of all foregoing searches, drawing logical inferences between them: If terms A and B have appeared together, and terms B and C have appeared together, Central Search concludes, then a researcher interested in A may also want to find C.

The tool excels at dredging up the kind of obscure vocabulary with which patents are littered. Input “SIM,” for example, and you’ll learn that patent writers use terms including Usim, uicc, m2m, and pimsi to discuss similar or closely related concepts. With intelligence from Central Search, we can speedily build queries that are both exhaustive and narrowly specific, zeroing in on investigative targets.

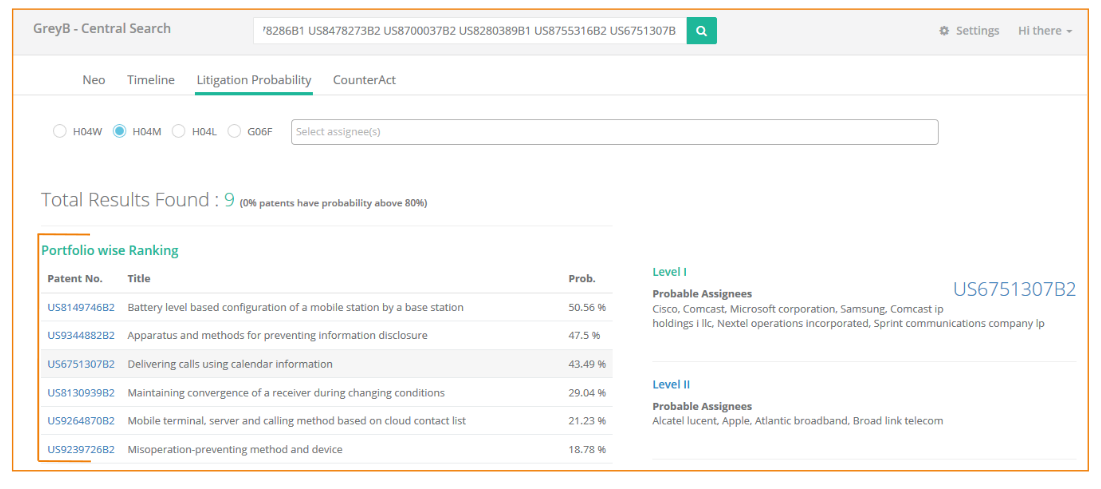

Litigation: Evaluating Sets of Patents Holistically

Companies often approach us to gauge the value (and potential value) of patent portfolios—their own, or portfolios that they’re thinking about acquiring. A third possibility is that the patents belong to one or more startups that the client is considering investing in.

Whatever the case, the key to this kind of assessment is analyzing the relative value of the patents’ underlying technology:

- What commercial space do the patents pertain to?

- What’s happening in that space?

- What does the direction of the industry seem to be?

- How new are the patents?

- How novel or disruptive?

- How frequently have the patents been cited?

- Are they involved in ongoing litigation?

It would be possible, of course, to conduct the evaluation piecemeal, analyzing the worth of each patent in a given portfolio one at a time—and to build, from those analyses, a comparison of the relative value of various patent portfolios.

But approaching the task this way would be haphazard and unsystematic, dependent upon the ability and expertise of a single analyst. Once a set of patent portfolios has been uploaded, Litigation evaluates them holistically, using a specialized algorithm that weighs the relative importance of various patent-value indicators to rank and analyze them for easy comparison. With the results in hand, our clients are well-informed about the value of their own portfolios and those of their competitors, allowing them to position themselves advantageously as new technology emerges from labs around the world—maximizing revenue and minimizing losses.

If you’ve been struggling with how to tackle your company’s IP research needs, and you’re interested in seeing the solutions that a machine learning-powered Investigative Approach could provide, you can contact us here.