“My client wants a fresh search on a patent about LED substrates” emailed an attorney – our repeat client – on a Friday.

“Of course, we can help you as this is relatable technology”, replied a new associate from our Sales team after having checked with me twice on a Friday night call, “We are really good in this, na?”

I told him, YES.

In fact, we are tending toward high on the confidence scale. My team worked on cases related to LED’s in the past too. In one of the cases, the firm we worked for was one of the top 10 patent litigation firms in the US. We have also worked on some cases where we invalidated patents (many were really tough!) owned by trolls in this space. A lot of these projects were on finding prior art like an old patent document, scientific literature, etc.

Other projects were about reverse engineering on LED substrates. I do remember one particular case where the end client was a design group in the organization. They desired to understand the processes used by competitors to get insights into achieving size, cost, power or performance targets. But that one is a story for another day.

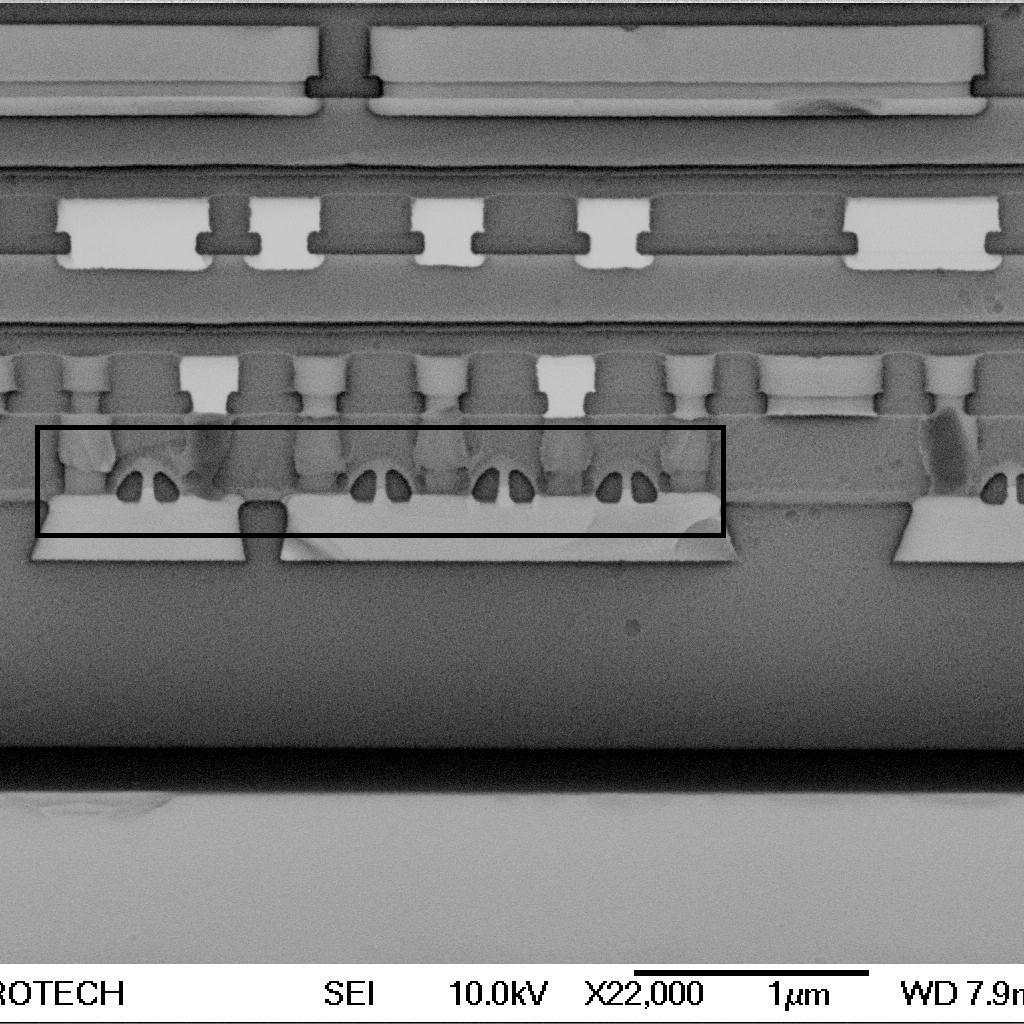

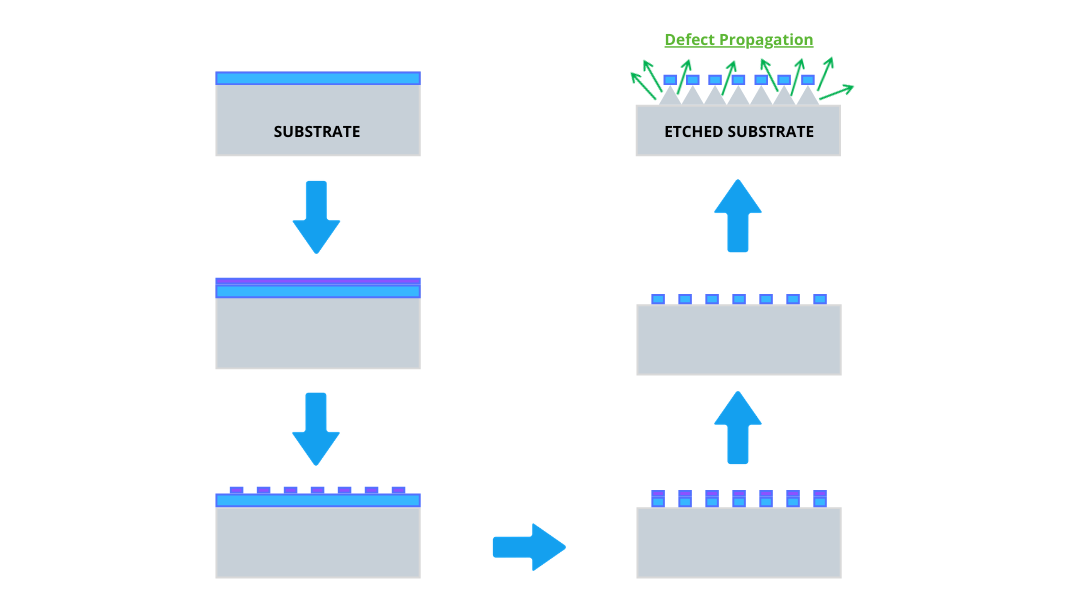

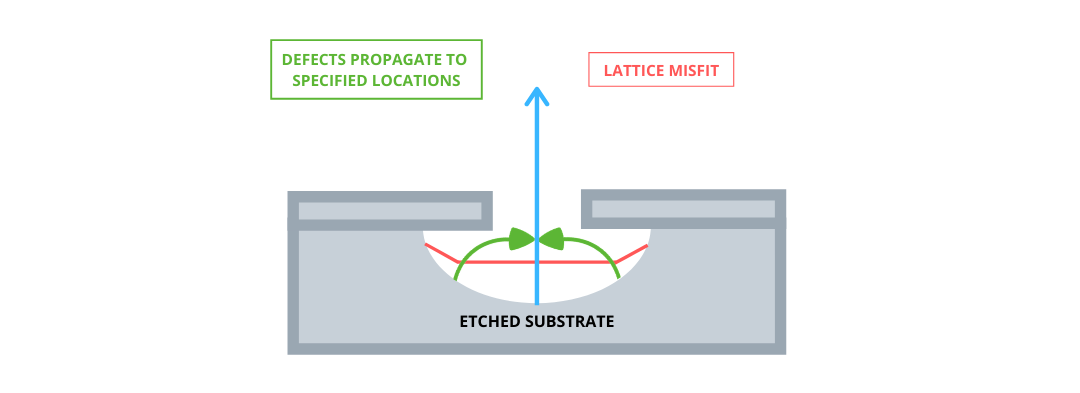

Come weekend and I got to know the client wants to start the project on Monday. More details were divulged. We figured out this particular patent was part of over 10 lawsuits and 4 PTAB petitions. Without going into ‘too much’ details, I will say the patent at high level claims the etching profile of the substrate. More specifically, how the specific profile helps to prevent defect propagation in the case of lattice misfit systems.

I am pasting the image below to give an idea of the topic of the search.

I am unsure how an attorney reads signs of past litigation history of the patent, but from a searcher’s point of view, two things were clear:

- This patent must be searched earlier if the history is of litigation. Things like – early cutoff date of the patent, claims are written in a way that prior art doesn’t turn up in earlier searches, prosecution arguments during grant were well positioned or not, etc.

- Routine searches must have failed to give something groundbreaking. The way of examiner search before the grant must have been (more or less) repeated in other searches.

I needed to think differently.

On Sunday night, I got a message from my manager. He wrote and I quote:

Before you start such a project, make sure you not only see, but you observe.

The distinction was clear.

The method I needed to adopt was to review the case in all its detail. Forget standard ways to search. I was encouraged to deal with the case as one that has never been seen searched before and work it out as a new problem sui generis. Try to figure out answers to questions like, how come the inventor thought of the problem to be solved?

I started my search journey.

Generally, the lattice misfit systems are required to fabricate large wafers for optoelectronic applications. The misfit system in the process often gives rise to dislocations thereby affecting the final device quality. To solve this problem, the inventive aspect of the target patent talks about how a curved etching profile helps to prevent defect propagation by guiding the defects to specific locations.

The asserted claim talks about the rotational etching profile and the micro-facet orientation. My target was defined.

A Look into the PTAB petitions

All the results submitted during the PTAB petitions focused explicitly on the substrate etching profile but were silent about disclosure regarding the micro-facets. The petitioners made arguments about the requisite micro-facet orientation would inherently be present. It made sense technically, but the courts didn’t agree. This was an interpretation and lacked more facts. None of the cases got instituted (Moreover, the courts had issues with the support for the substrate etching profile).

As expected, the search was a tough one. Most of the search findings were trying to solve the similar problem of the patent but using slightly different techniques. The search team was upset.

Imagine you are getting so close to a good result and then you notice a small difference in the technique. It is frustrating.

Perhaps that is why the client came to us. GreyB knows the difference between a prior art and almost prior art. We expanded the scope of the search. We looked into the different methods and eventually identified a couple of good results targeting the substrate etching profile.

On the other hand, we had nothing to show for the micro-facet orientation. We even aimed to search this independently. We wanted to present the case of a combination/obviousness approach. But again, our search was not giving results above a threshold.

This is exactly the point where most of the search firms give up. This point, often called, end of the tunnel, makes the searcher believe that even with a different combination of the search strings the same results show up. You should know, GreyB doesn’t give up here.

This is the most critical point of search. At this point, the science of search changes into the art of search and we love this switch.

We started with a fresh mindset. In another round of review of the patent specification, I observed something. The use of a particular H2SO4 based isotropic etchant is responsible for effecting the micro-facet orientation as claimed by the patent. I revised my search approach. I specifically searched for this etchant in the context of LEDs.

Boom! I came across a few results and one particular result captured my interest.

This result was not explicit about the micro-facet orientation. But the suggestion of using the same etchant made me develop the logic. We suggested to the attorney our argument to challenge the validity. There was some back and forth communication and we were able to present the case effectively. The attorney found this to be a new way to challenge the patent.

In a post-delivery connect, the attorney sounded happy. He specifically asked, “What made you think to go in this direction?”

I responded, “We just made sure we don’t make one error in the search process”.

“What is that error?” asked the curious attorney.

“You see, but you do not observe” and I laughed.

The client appreciated the thought process. With a grin, he gave us really positive feedback and additionally, a reference within his firm.

Want us to conduct a good patent search for you?

Next Step: Here are the other Patent Invalidation Case Studies just in case you want to read more.

Authored by: Prateek Gandotra, Prior Art and Nidhi, Market Research.