At GreyB, companies often approach us with the broad objective of having us help them strengthen their IP position. It’s a challenge that incorporates elements of the three core IP research sectors—finding prior art, patent analytics, and patent commercialization—and often involves creating a comprehensive patent strategy. Depending on their focus areas and preferences, businesses choose to build their patent portfolios at various stages in their development. But the reasons that companies—both established behemoths and feisty startups—find it necessary to strengthen their IP generally fall into two basic categories:

- Developing a strong defense against lawsuits and licensing demands

- Getting an innovative edge on competitors

Allowing the competition to pull away (2), of course, can spell doom for even a powerful company, and fees and fines arising from IP licensing and lawsuits (1) can easily cost a large company many millions of dollars a year. These represent two major causes of (entirely justified) anxiety for a growing company. There’s also the fact that the best defense is often a good offense when it comes to intellectual property. A company with a robust, well-designed patent portfolio is well-positioned to countersue in the event of a patent infringement lawsuit brought by a competitor. They’re, therefore, much less likely to be sued in the first place. In this article, we’ll outline four effective tactics for building IP strength that work well in various scenarios. In combination, they can amount to a powerful strategy for both getting an edge on their competitors and limiting IP-related losses:

- Patent acquisition

- Company acquisition

- Talent acquisition

- Collaboration

We’ll also explain how we help companies identify and evaluate unmet market demand to create innovative strategies, strengthening their IP position amid a shifting technological and economic landscape. But first, let’s talk more about why developing IP strength is so important.

A Lesson From Uber: IPOs, Lawsuits, and Licensing Demands

In recent years, some of the buzziest tech firms in the world have made their name not by coming up with trailblazing technology but rather—in large part—by quickly seizing a huge portion of their market. The ride-sharing companies Uber and Lyft are prime examples—Airbnb is another—and it was, of course, (mostly) by providing a service that many consumers wanted that they managed to gain a strong market share.

But their products were also a function of their time, made possible by the era of technological evolution in which the companies were founded. Likely without meaning to, Uber and Lyft built their businesses partly by using IP—related to navigation, route planning, etc.—that technically belonged to others. Which is to say, by patent infringement. That put them in a vulnerable position.

Large companies—which often have vast patent portfolios containing hundreds, if not thousands, of patents, spread across various tech sectors—can generate billions of dollars in annual revenue simply by licensing their tech to others and suing companies that have infringed on their patents. Prominent examples of this model include Microsoft, LG, and Apple. That’s bad news for a frequent infringer like Uber. And as if becoming the target of a company like HP or Google weren’t enough to worry about, there are also the non-practicing entities, or shell companies, that accumulate IP to monetize it via fees and lawsuits.

When Uber and Lyft were founded, in 2009 and 2012, respectively, they made unlikely targets for IP owners looking to monetize their patents; there’s little point in suing a relatively anonymous company with limited resources. But that began to change in 2013. By that year, Uber and Lyft were generating considerable excitement in the market, and capital from investors was flowing in, making them increasingly attractive targets for IP owners. That year, both firms were sued by Electronic Communication Technologies LLC. Since then, IP lawsuits against both ride-sharing companies have come fast and furious; in 2019, Uber was already sued by five separate companies.

In May of 2019, Uber made its IPO, and the fact that the company has been the subject of so much legal action this year reflects a well-known pattern: patent infringement lawsuits against a company tend to ramp up immediately after their IPO—and the influx of capital that comes with it. But common knowledge notwithstanding, we’ve noticed that the increase in lawsuits actually often begins after the IPO is announced but before it takes place. This makes good, if cynical, sense.

When Uber’s IPO was announced, it became extremely sensitive about its reputation like any well-known company in the same position.

Bad press could lead Wall Street to devalue the company, reducing its eventual price-per-share. Getting tied up in a new lawsuit is likely to generate negative publicity, so companies on the cusp of an IPO are often incentivized to quash litigation as quickly as possible. Naturally, this is true, especially for companies that don’t have strong IP portfolios and therefore stand little chance of effectively defending against a lawsuit. It’s at this point that non-practicing entities may sue such companies.

By the time Uber was preparing to go public, they’d made an effort to fortify their position, drastically increasing the strength of their IP holdings by amassing more than 400 patent families. Each family, or group of patents, protected a single invention. That was up from just 37 patent families a few years earlier. But big companies sometimes initiate IP lawsuits before an IPO, too, and Uber’s progress wasn’t enough to discourage Google, which ultimately accepted a $245-million settlement from Uber for infringing on technology that belonged to its subsidiary, Waymo.

It is difficult to say what effect the settlement had on Uber’s share price, which disappointed expectations, but it generated huge headlines. And although settling litigation before an IPO is often the best choice for a company with a less-than-fearsome patent portfolio, it is not generally an enviable option.

Hastily settling IP lawsuits in the run-up to an IPO makes a company look weak. It’s a tacit admission that they’re in the business of selling products or services based on ideas or inventions that don’t belong to them. To anyone analyzing the company’s value, however large their market share, that’s not an encouraging sign.

Had Uber begun strengthening their IP position earlier, it might have been able to hold fast against Google’s lawsuit, demonstrating to observers that they were confident in the solidity and value of its own intellectual property. Below, we’ll discuss how we might have advised them to do that, using a combination of short and long-term tactics to enlarge, improve, and bolster both their patent portfolio and the innovative firepower of their team.

In the next section, we’ll detail a high-profile case in which a longstanding retail giant initiated a campaign to quickly improve their IP’s competitiveness. But if you’d like to skip straight to the strategy part of the article, you can click here.

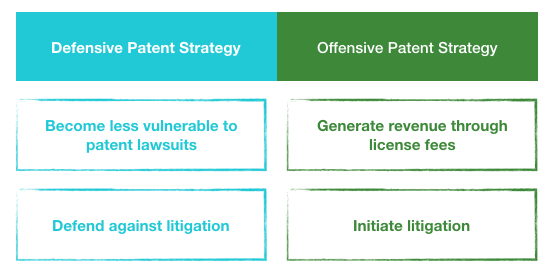

Another Approach to IP Strategy: How Amazon and Walmart Show Why Following a Competitor’s Lead Often Makes Sense

Developing a patent portfolio with the primary purpose of decreasing one’s vulnerability to legal challenges is what’s known as a defensive patent strategy. If their business involves IP, almost every company of a certain size is going to want—read: need—one. Getting sued is bad for business, IPO or no IPO. But many companies are also interested in creating an offensive patent strategy that will allow them to generate revenue through patent licensing fees and patent infringement litigation that they initiate, which also often helps them get a leg up on—or catch up to—their competitors.

For the vast majority of companies, it’s not an either-or situation. Offensive and defensive patent strategies can and should be considered complementary and mutually reinforcing.

But devising a patent strategy that focuses on breaking new ground can be tricky. These days, companies in virtually every industry trip over one another to brand themselves as the most innovative around. Many of them back it up, pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into R&D. But although everyone is certain that they need to innovate, more often than you might think, companies lack a clear idea of how to direct their creative energy. That is, they’re unsure what they should work on inventing.

As far as we’re concerned, figuring out the answer involves a complex, multistep process. We use it to guide our clients to the right path for them, and we’ll detail the process later in this post. But big companies often design strategies to strengthen their IP position by taking queues from competitors.

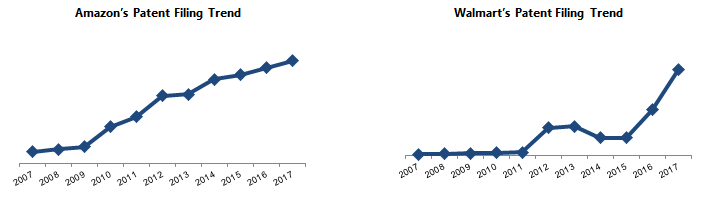

In 2017, when Doug McMillon, the president and CEO of Walmart, told shareholders that the retail giant had “started to invent the future of shopping again,” leveraging technology to do things like optimize “last-mile” delivery and expand grocery-related offerings, he was referring in part to a progressive emphasis on IP development that Walmart initiated in earnest around 2015.

Until then, Walmart’s patent filings had been both limited and static, except for a slight uptick in 2011. And by looking at a side-by-side comparison of patent filings by Walmart and Amazon—as well as by taking into account the general shift in Walmart’s business—it is not difficult to conclude that Walmart’s executives decided to model Amazon’s tactics at some point.

After all, as the graph above shows, Amazon had once been merely an e-commerce platform with a weak IP position to boot. It wasn’t until 2009, fifteen years after the company’s founding, that they began filing patents quickly. The change prefigured Amazon’s transformation into the multi-tentacled, trillion-dollar “everything” company they’ve become. (That’s not to say, of course, that Jeff Bezos was subsisting on ramen noodles until ‘09.)

The fact that Walmart, a brick-and-mortar retailer founded in 1962, was slower to ramp up its IP than Amazon, an Internet native, is hardly surprising. And for a large company in the retail/e-commerce space, there are certainly worse models for success than Amazon. It’s not enough to simply be a copycat, but by analyzing the course successful competitors have taken based on their patent filings, a company can glean valuable intelligence with which to chart its own future.

Accordingly, when companies approach us for guidance about how to kickstart their patent portfolio, particularly when they’re a bit behind the curve, innovatively speaking, our first suggestion is very often to conduct a patent landscape analysis. It’s a specialized process that gives an overview of all the extant and pending patents related to a given sector or industry—a snapshot of what all of the other companies working in a given area are focused on. In the following section, we’ll explain why and suggest some good next steps.

How Patent Landscape Analysis Can Help Companies Build Their Patent Portfolios to Strengthen Their IP Position

Whether a company looking to improve its IP strength wants to pursue a defensive patent strategy, an offensive patent strategy, or to take big, moonshot swings in its R&D department (or all of the above), understanding the lay of the land is essential to devising a plan of attack. Like most other IP research tasks, an effective patent landscape analysis is based on a powerful digital search, in this case, limited to patent databases. An imperfect search will skew the resulting landscape and is all but certain to mislead anyone trying to use it as a guide.

Digital searching might sound straightforward enough, but as we’ve written previously, navigating the free and subscription-based databases where patents are stored online demands a particular kind of expertise. At GreyB, we use machine learning tools to ensure that our searches are maximally comprehensive. And you can read more about our patent analysis landscaping process here, in a deep-dive on an analysis we recently conducted of the smartwatch industry.

A well-executed patent landscape analysis of a given industry or sector, however, will definitively answer some key questions:

- How many patents have been filed?

- How many have been granted?

- When, where, and to whom?

- What technologies do they concern?

With these answers in hand, a company can begin thinking strategically about how to augment its own patents to best position itself in light of current innovative and economic conditions. Often, especially in the early stages of creating their patent portfolio, companies—even large ones—focus almost exclusively on developing IP in-house. Good R&D is vital, and we would never discourage a company from funding it aggressively. But there are several other options for growing a patent portfolio, all with unique advantages. For most companies, mixing and matching to answer different challenges is the best strategy.

Patent Acquisition

Building IP strength through patent acquisition—buying patents—has much to recommend it. And one of the many advantages of conducting a patent landscape analysis is learning who owns what patents. After we do a landscape analysis on behalf of a client, they can use the intelligence we’ve gathered to approach the relevant patent owner(s) about the possibility of a deal.

Largely because of the frenzy of innovation we mentioned earlier, companies with big R&D departments often end up owning hundreds of patents that don’t pertain to their products or services and which aren’t otherwise particularly useful to them—except as merchandise—and they’re more than happy to sell. But it’s not enough to acquire any old patents. And based on our client’s strategy, we will evaluate the patents in a given landscape to determine their relative strength and make recommendations for acquisition.

If a company is afraid of getting sued, like Uber in the example above, we will calibrate our analysis to identify patents to patch weak spots in their portfolio—patents covering technology that they use or are likely to use and which could make them vulnerable to attack in the hands of another owner. Alternatively, if a company wants to pursue an offensive patent strategy, we will identify patents that overlap with tech that one or more large company is already using and which could be easily monetized through litigation or licensing fees.

For a company that has to build IP strength quickly—if they’re planning an IPO, for example, and need a defense against potential lawsuits—patent acquisition is often the best route. The process of developing and patenting technology can take many years, and the results are uncertain. Through well-advised patent acquisition, companies can quickly target and purchase exactly the patents that fit their needs, preferences, and strategies. It’s also often cheaper than developing IP in-house.

A portfolio containing ~40 patents might easily come with a price tag of $5 million (or more), which can scare off executives unversed in the IP marketplace. But in addition to cutting R&D costs to zero, buying extant patents eliminates the legal expenses associated with the process of applying for and getting patents granted, which can run to $30,000 for each patent. For 40 new patents, that’s $1.2 million in legal fees up front, with no guarantee of the patents’ ultimate value. Meanwhile, a single patent, well-chosen for acquisition, can easily be licensed for $5 or $10 million annually.

Company Acquisition

Building IP strength by buying up whole companies rather than individual patents or patent families—groups of patents pertaining to a single invention—comes with many of the same benefits outlined above. But it also has some additional advantages, leading some companies to prefer this tack.

Buying a whole company gives the purchaser access not only to the IP belonging to the newly acquired firm but also to that firm’s talent, facilities, and geographical presence. If a company wants to move into an area of tech development that they’ve yet to enter, for example, a targeted corporate acquisition that comes complete with relevant labs, equipment, and in-the-know engineers might well make better sense than IP acquisition alone. (There’s a reason that Apple favors this strategy.)

Similarly, if a company wants to venture into an emerging market—Africa, say, or Latin America—in which it does not currently have any experience or physical presence, finding a firm to buy that already has boots on the ground makes for a savvy approach.

Talent Acquisition

Talent acquisition—sourcing great minds from labs and universities to bolster an R&D department or poaching them from competitors—is a longer game than building IP strength by purchasing patents directly or via corporate acquisition. But one needn’t look further than companies like Apple and Google to see that when done well, it makes for a stellar long-term strategy. Indeed, it’s largely because non-compete clauses are illegal under California law—and the company-hopping that the prohibition promotes—that Silicon Valley has long been a hub of technological innovation.

Knowing how and where to acquire talent can be challenging, though, and at GreyB, we recently designed software to help us guide our clients to the most promising prospects. A tool that draws on our expertise in patent searches, it acts as a kind of scout, allowing us to identify scientists and engineers around the world through name, country, industry, company, and sector-based searches, among others. By providing an in-depth accounting of all of the patents a given prospect has worked on, the tool allows us to evaluate their technical ability, creativity, and intelligence—invaluable data for a company seeking to bring in new blood.

The software also indicates how often a potential hire has changed jobs, suggesting their relative receptivity to an offer. Of course, an engineer who’s prone to jumping ship might well be inclined to leave whoever their next employer happens to be high and dry, too.

Collaboration

Companies that are still in the process of developing and honing their core technologies generally aren’t interested in collaborating on IP. They’re wary about the possibility of trade secrets leaking, devaluing their hard-won tech advances. That attitude isn’t hard to understand.

Once a firm has firmly established its lane, however, and it’s time to develop ancillary products and services, collaborating with outsiders can be beneficial. Sometimes competitors collaborate, pooling their resources in some mutually beneficial R&D venture. More often, though, companies collaborate with academic partners—generally big universities with substantial research facilities and plenty of brainpower to bring to bear. Toyota, for example, is a co-assignees in more than 25,000 patent families that are the product of collaboration.

By outsourcing research, companies can dramatically reduce the overhead of building and staffing lab facilities. It’s also smart to pursue new and/or less-than-certain research routes. As ideas and inventions develop inside a university lab, the partner company can track the growth, shifts, or shrinkage of the relevant domain, calculating how best to proceed without being too dearly invested in the results of the research. If the domain looks like it’s poised to flourish—self-driving cars, say—the company can move to pursue related IP in-house aggressively. If not—self-vacuuming cars, for instance—they can walk away.

Using powerful digital searches of databases containing a wide variety of IP literature, we regularly help companies identify universities and researchers that would make appropriate collaborators for their needs. In combination with savvy patent and talent acquisition, it’s an excellent tool for building long-term IP strength.